As I write THIS ARDENT FLAME, set in northern Vermont in 1852, I spend a lot of time in research -- but not just exploring this pre-Civil War decade of ferment. In order to understand the thinking and discussions of the time, I often backtrack to the War of Independence and the strong-minded individuals who voiced their dreams for this new nation, built from a set of very different colonies and then growing by annexation of territory (and almost always while ignoring the history and rights of Indigenous peoples).

This week I'm reading Compassionate Stranger: Asenath Nicholson and the Great Irish Famine, by Maureen O'Rourke Murphy. One reason to read the book is as background for how the characters in THIS ARDENT FLAME deal with the Irish immigrants arriving in Vermont at the time. Another is that Asenath Nicholson, an activist of the first half of the 1800s, was born and raised in Chelsea, Vermont, not far from the Northeast Kingdom. (I've spent many hours there as the mom of an actor in a Jay Craven/Howard Frank Mosher film. Where the Rivers Flow North.)

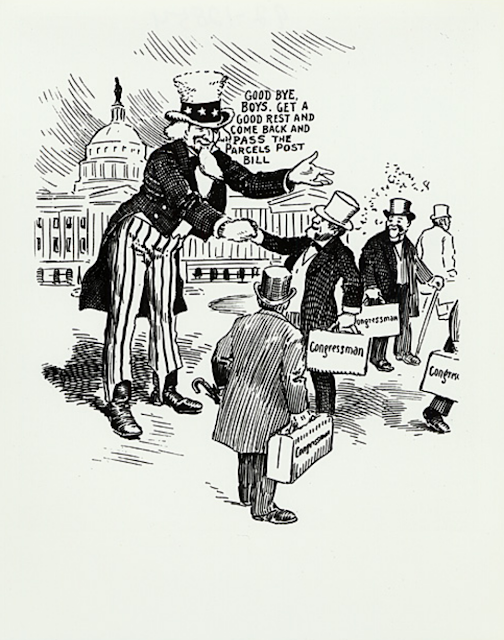

Every detail in the book takes me digging for more details elsewhere, and this morning I "dug into" Sunday mail delivery. I was surprised to learn that it was routine in our nation's first century: It was considered essential for commerce! Moreover, the 1820s/1830s movement to end Sunday mail delivery came out of a small group with religious passions and especially religious bias -- against those Irish and other Catholic immigrants, who often used their "day of rest" to feast, gather, and rejoice, rather than to endure the silent solemnity of a Puritan-style Sabbath.

The post office with its mandatory Sunday opening (required by law to be open at least one hour each Sunday) became a social location. Not only did men gather there to pick up their letters and commercial orders, but they also often sat down to socialize, drink, and play cards. This horrified those who took their Sunday worship more seriously. Interestingly, these horrified individuals were often the same ones pursuing the Abolition of slavery, out of the same Christian beliefs!

Thus, Arthur Tappan, an ardent abolitionist of both New York City and New Haven, CT, would raise as much anger by his "Sunday mail laws" campaign as by his campaign to end slavery, and his brother Lewis, campaigning the same way, had his house broken into in 1834 by an angry mob.

Only 7% of the nation claimed strong religious ties at the time, and most opposed shutting down the post office on Sundays. The invention of the telegraph in the 1840s would ease the commercial necessity of Sunday mails. But the legislation to close the post office on Sundays would not be passed until 1912, and part of the opposition to it lay in favoring one religion over another, counter to the definitive statement of the Constitution that insisted the new nation not pick and choose. (Arguments included the belief that Sunday closing of the postal service would then lead to Saturday closing on behalf of the Jewish Sabbath, to be fair!)

What eventually tipped the nation to passing the closure laws was a combination of two pressures: postal workers wanting a day off like everyone else, and trading the closure for the new service of Parcel Post: being able to handle packages routinely.

That's a lot to think about, in the context of this week's political talk about Amazon, postal rates, and Sunday deliveries that have now resumed!

Vermont author Beth Kanell is intrigued by poetry, history, mystery, and the things we are all willing to sacrifice for -- at any age.

Wednesday, December 26, 2018

Sunday, December 9, 2018

Crossing Paths with Franklin Benjamin Gage of East St Johnsbury

Although it's barely a whistlestop* now, with just a post office and a church and a "free library" on the post office porch -- plus the significant Peter and Polly Park, which I'll write about at another time -- East St Johnsbury was once a hub of manufacture and business. The significant Fairbanks family that nurtured both jobs and culture for the area erected its first mill on the Moose River in East St Johnsbury. Actually in the early days this was "St Johnsbury East" or just "East Village." And it prospered.

That prosperity and the related emphasis on education were in the background of a youth named Franklin Benjamin Gage, born in the village in 1824. He became a significant inventor in photo processes, and created both portraits and landscape images. I'm enamored of his stereo views of the region, which have become hard to find.

Shown here is a child portrait -- could it be your great-great-great-grandparent? -- probably made in Gage's studio in St. Johnsbury proper. On the reverse, he calls it an "ebonytype": a fancy name for a way of presenting the work that may have emphasized the sharp contrast of black and white in the original portrait. It's hard to tell now ... "ebonytype" doesn't have a definition that I've found, and is only mentioned in a wonderful article on Gage, from which I draw this quote:

If this IS your four-greats grandparent, please do let me know. I'd love to attach a name to the face.

*Whistlestop: a railroad term. Also pertinent to the article I spent yesterday researching and drafting. You'll see it soon.

[Thanks, Dave Kanell, for the images!]

That prosperity and the related emphasis on education were in the background of a youth named Franklin Benjamin Gage, born in the village in 1824. He became a significant inventor in photo processes, and created both portraits and landscape images. I'm enamored of his stereo views of the region, which have become hard to find.

Shown here is a child portrait -- could it be your great-great-great-grandparent? -- probably made in Gage's studio in St. Johnsbury proper. On the reverse, he calls it an "ebonytype": a fancy name for a way of presenting the work that may have emphasized the sharp contrast of black and white in the original portrait. It's hard to tell now ... "ebonytype" doesn't have a definition that I've found, and is only mentioned in a wonderful article on Gage, from which I draw this quote:

The highly researched piece on Gage is authored by Bill Johnson and Susie Cohen -- I don't know who they were/are, and they stopped posting their writing about vintage photos five years ago. But I keep returning to the article, and now it has added meaning because the prime of F. B. Gage's life overlaps the period that's coming to life in my in-progress book, THIS ARDENT FLAME (second in the Winds of Freedom series from Five Star/Cengage). So I am thinking about what Gage may have seen in this image, and why he chose it to promote his work.By 1856 Gage advertised that his was the largest photographic establishment in the state of Vermont; at first offering daguerreotypes and then adding all the modern processes and styles as they became available – ambrotypes, mezzotypes, ebonytypes, cartes-de-visite, cabinet portraits, and so on, as well as displaying and selling his stereo views.

If this IS your four-greats grandparent, please do let me know. I'd love to attach a name to the face.

*Whistlestop: a railroad term. Also pertinent to the article I spent yesterday researching and drafting. You'll see it soon.

[Thanks, Dave Kanell, for the images!]

Tuesday, December 4, 2018

Ruffed Grouse, or Partridge (Pa'tridge)?

One of the challenges of writing a novel set in 1852 is the details that aren't recorded, but that I still want to get "historically accurate" for the story. Today's puzzlement is how to talk about the wild bird known to American colonists, based on their British experience, as partridge -- but corrected in name to ruffed grouse. John J. Audubon painted the birds (see above). And Karen A. Bordeau of the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department also wrote this in 2015:

And the New International Encyclopedia of 1917 says this:

So, what do my characters call these birds? That's in chapter 4 of THIS ARDENT FLAME (Book 2 of Winds of Freedom).

Regulation of grouse hunting received no attention for a long period. The first act protecting birds was passed in 1842, affording a breeding and rearing season free from molestation. They could be legally taken between September 1 and April 1, and permission of the landowner was required for hunting.

The regulation was repealed after four years, and grouse remained unprotected until 1862. The second law protecting grouse, passed in 1862, established a shorter season – September 1-February 28 – and four years later hunting was further curtailed by closing the season on January 31. Snaring had been a popular method of capture, and in 1885, was forbidden. By 1929, grouse were so rare all over the state that the Legislature completely closed the season in Coos County on the Canadian border, and in Cheshire County bordering Massachusetts.

And the New International Encyclopedia of 1917 says this:

So, what do my characters call these birds? That's in chapter 4 of THIS ARDENT FLAME (Book 2 of Winds of Freedom).

Sunday, December 2, 2018

Review of THE LONG SHADOW in Vermont History, Summer/Fall 2018, Social Studies Focus

One of the best tests of a historical Vermont novel with teen protagonists takes place when a social studies teacher -- a professional in the field -- sits down to read it. So I am hugely grateful and honored that Christine Smith, a teacher-librarian at Spaulding High School in Barre, Vermont, and president of the Vermont Alliance of the Social Studies (VASS), chose to read and review THE LONG SHADOW for the summer/fall 2018 issue of Vermont History, the journal of the Vermont Historical Society. I'm posting the review here -- seeing this in print is one of the great benefits of being a member of the Vermont Historical Society. Other articles in this issue focus on Burlington's ethnic communities, a Vermont steamboat pioneer, and Revolution-era hero Seth Warner. All worth reading!

My Brain Is Back in 1852 (Writing THIS ARDENT FLAME)

Dishes are stacked a little higher than usual. There's dust under the bed. But the chapters are unfolding, each page a marvel as I "discover" where the new book is going. My feet and my brain are in 1852 (fear not, my heart's still with my honey in 2018, and I can still cook).

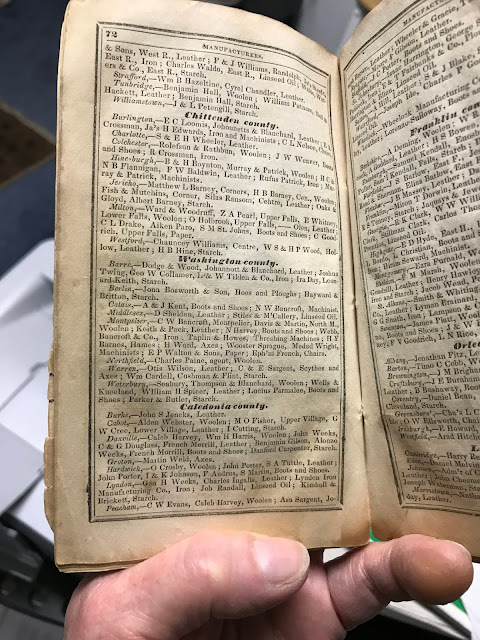

Just so you can see what it's like -- at one moment I'm tapping out dialogue and moving the characters to the next scene. And then, quick, it's time to dash back into the research, like these marvelous pages from the 1854 edition of Walton's Register -- a business directory for Vermont that reveals much, much more than who owns what.

Just so you can see what it's like -- at one moment I'm tapping out dialogue and moving the characters to the next scene. And then, quick, it's time to dash back into the research, like these marvelous pages from the 1854 edition of Walton's Register -- a business directory for Vermont that reveals much, much more than who owns what.

Thursday, November 8, 2018

Which of These Did You Read as a Teen?

What makes a book into a good one for "young adults" or "middle

graders"? When do adults start reading those same titles? This and more,

on Saturday as I take part in "Writing for the Younger Set," a panel at

the annual conference of Sisters in Crime New England. Here's what I have in mind ...

-->

Writing for the Younger Set – Notes from Beth Kanell

In the 1800s, “Books for Young Persons” included The Swiss Family Robinson, Waverly (Walter Scott), Oliver Twist (Dickens), The Count of Monte Cristo (Dumas), Great Expectations, Alice in Wonderland, The

Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Kidnapped

(Stevenson), and Kipling’s The Jungle

Book. According to a Wikipedia author, these were books that “appealed to young readers, though not necessarily written for them.”

In the 1960s, the market for “adolescents” blossomed – and

in 1973 Deathwatch by Robb White won

the Edgar Award for Best Juvenile Mystery. I’ve heard it said often that the

true impetus of the “young adult” genre came from librarians, who saw a need

for good books that wouldn’t push young readers into areas that were too mature

for them.

But in the 1980s, that taboo was broken by books that dealt

with rape, suicide, parental death, and murder – perhaps more at the YA (young

adult) level than for middle grades (MG). With this trend came the teen romance

novel, wrapped in adventure and with a more frank sexuality, even if the

characters “resisted.” Contrast this with the Lord of the Rings trilogy, long a

favorite among teens but containing no sexuality at all!

The Harry Potter series and the Hunger Games trilogy broke

the barriers down further, making it clear that the important cultural

questions, when addressed in fiction, could command a mixed audience of middle

graders, young adults/teens, and adults. A book positioned deliberately for

such a mix is now called a crossover – especially prominent today are “YA

crossover” books, intended for adults as much as for teens.

Some aspects of writing “YA crossover” that intrigue me

within the history-hinged mystery area are:

* The protagonist is a teen and thus by definition not very

experienced – which leads to an “unreliable narrator” in a good way.

* The emotional value of the book comes with the teen’s

confrontation with the world in some form, leading to “coming of age” – maybe

not all at once.

* Issues that adults think are obvious or settled become

open to new experience for teens: racial injustice, gender walls, technological

windows, even illness and death.

I also spend a lot of thought and energy on issues around

“who speaks for whom” and the amounts of violence and explicit physical

awareness (which includes sexuality) when I write.

Most deeply, I believe the writer for young adults owes the

audience three things: integrity, a chance to reach different conclusions than

the writer’s, and a sense of hope for the future of each individual.

Beth Kanell lives

in northeastern Vermont, with a mountain at her back and a river at her feet.

She writes poems, hikes the back roads and mountains, and digs into Vermont

history to frame her “history-hinged” mystery novels: The Long Shadow, The Darkness

Under the Water, The Secret Room,

and Cold Midnight. Her poems scatter

among regional publications and online. She shares her research and writing

process at BethKanell.blogspot.com.

(for November 10, 2018)

-->

Tuesday, September 25, 2018

If Everyone in America (and Specifically, Vermont) CAN Vote Now, Why Don't They?

|

| Alice Stokes Paul (1885-1977), in 1917 -- and a view of today's meeting in Vermont. |

In the year 2020, we'll mark 100 years since American women gained the right to vote. For some of us, exercising our vote came as a normal mark of adulthood -- and in Vermont, when we sign up to vote also pledge to do it responsibly, using the Freeman's Oath, which in 2002 became the Voter's Oath and gained inclusive language:

§ 42. Voter's qualifications and oathsIs voting any different for women than for men? Percentages of voting women suggest there are real effects of gender ... hard to sort out. Even more than gender today, though, access to voting can be blocked or slowed by disability (I have a sibling whose lack of mobility makes it REALLY hard to get registered), low income (who'll watch the kids? what about loss of pay for that hour off to sign up, when every hour of income matters?), and details like skin color, accented English (even if the person is very educated), and obvious personal choices and beliefs can all interfere.

Every person of the full age of eighteen years who is a citizen of the United States, having resided in this State for the period established by the General Assembly and who is of a quiet and peaceable behavior, and will take the following oath or affirmation, shall be entitled to all the privileges of a voter of this state:

You solemnly swear (or affirm) that whenever you give your vote or suffrage, touching any matter that concerns the State of Vermont, you will do it so as in your conscience you shall judge will most conduce to the best good of the same, as established by the Constitution, without fear or favor of any person.

Today's Montpelier meeting of about 18 women (some in person, some phoning in) to collaborate on preparation for marking 2020 included conversation about most of those factors. It also admitted past detours, with resolve for better present and future actions. The interactions, energy, and respect in the conversation promised an effective mission, strong goals, and exciting events and processes ahead. I learned a lot about how active the League of Women Voters is in Vermont, too, with strong effects that can create change.

Consider this set of mission plus goals from 25 years earlier, in Vermont, to mark 75 years of women voting -- where I was surprised to see the economic focus:

I also learned about a Vermont organization called Change the Story -- came home wearing a pin provided via the Vermont Commission on Women, and checked out the website (http://changethestoryvt.org), discovering the group focuses on the economic status of women in Vermont. Makes sense to me ...

I can hardly wait to see what comes next!

Sunday, August 19, 2018

House of Dreams: The Life of L. M. Montgomery, by Liz Rosenberg

It's daunting to realize how many books and stories L. M. (Lucy Maud) Montgomery wrote, often under conditions of enormous financial or emotional stress, and how well loved they became. This year's biography of the author, by professor and novelist Liz Rosenberg of Binghamton, New York, concludes with a description of the reach of Montgomery's beloved character Anne of Green Gables:

The popularity of L. M. Montgomery's writing continues unabated. Maud's books have sold millions of copies. Her work lives on in dozens of forms -- some of which she never knew, and could not have even imagined. Her writing has been successfully adapted to the stage, the movies, and for television, and is available in books, CDs, and DVDs. Discussions of her work abound in journals dedicated to her writings, and in online blogs and articles.Let that be a noted talking point for those explaining the lasting and global effect of children's books and classics about growing up poor and making the best of things. As Rosenberg demonstrates in HOUSE OF DREAMS (a title that reflects the 1917 "Anne" book, Anne's House of Dreams), one persistent and naive author who puts pen to paper every day can eventually see her stories enter the hearts of astonishingly diverse people.

Anne's House of Dreams was distributed to Polish soldiers during World War II to lend them courage and hope. ... Prince Edward Island estimates 350,000 come to visit Green Gables each year. Kate Middleton, as the newlywed wife of Prince William, flew to Prince Edward Island on her honeymoon in honor of the books, citing Montgomery as one of her favorite and most influential authors. ... Her works are treasured by children and adults all over the world -- they are particular favorites of Japanese schoolchildren, fellow islanders living half a world away. ... Her single most beloved and famous book, Anne of Green Gables, has sold more than fifty million copies worldwide and been translated into more than twenty languages.

Rosenberg is a poet and novelist, as well as biographer, and these qualities enable her to narrate Maud's own life of heartbreak with passion, insight, and a sense of pace that feels like a well-spun novel, full of complex characters and twists of plot. Trapped in a dysfunctional family through both poverty and her own sense of loyalty to her grandmother -- a brusque and stern woman who nonetheless made enormous sacrifices so Maud could gain an education and become employed -- this lifelong writer created the personality of an orphaned girl with unfortunate red hair, determined to see and name the beauty of the world around her.

There is certainly a circle of courage in Montgomery's "work and life": The character she gave to Anne connected directly to the better days of her own spirited approach to life. But unlike her protagonist, Maud Montgomery had very few "lucky breaks" in life. Repeatedly "orphaned" in terms of people who should have taken care of her as a child, then disappointed in love and entangled with men whose coping strategies tore her apart, she still maintained her discipline of writing, and fought for publication of her work. At one point one of the most highly paid authors among Canadians, she also saw her work become profitable to an unscrupulous and unpleasant publisher (she did not benefit from the vast earnings of the "Anne" films), barely coped with what was probably bipolar disorder, and gave up her peace of mind as well as her fortune to take care of the (mostly) men who depended on her.

There is certainly a circle of courage in Montgomery's "work and life": The character she gave to Anne connected directly to the better days of her own spirited approach to life. But unlike her protagonist, Maud Montgomery had very few "lucky breaks" in life. Repeatedly "orphaned" in terms of people who should have taken care of her as a child, then disappointed in love and entangled with men whose coping strategies tore her apart, she still maintained her discipline of writing, and fought for publication of her work. At one point one of the most highly paid authors among Canadians, she also saw her work become profitable to an unscrupulous and unpleasant publisher (she did not benefit from the vast earnings of the "Anne" films), barely coped with what was probably bipolar disorder, and gave up her peace of mind as well as her fortune to take care of the (mostly) men who depended on her.The only time that I was able to "put aside" HOUSE OF DREAMS was when I just had to stop to quickly re-read Anne of Green Gables, to feel again the marvelous joy of Anne's self-propelled discoveries of love and life. Then I plunged back into HOUSE OF DREAMS, unwilling to interrupt it again, even through the massive sorrows of Montgomery's pathway.

Many thanks to Rosenberg for this satisfying addition to women's biography, to the insight that an author's life can provide, and to opening a door for younger readers -- from engaged 12-year-olds on up -- to explore how an author and her work can braid and mingle. The publication of this volume by Candlewick Press, with its esteemed standing in libraries, classrooms, and bookshelves of eager readers, makes that intent especially clear. And the tender line drawings by Vancouver, BC, artist Julie Morstad are a perfect match to the book.

I plan to stay grounded in HOUSE OF DREAMS as I set "pen to paper" for my own next novel. What an inspiration to treasure! I'm on my way.

Tuesday, July 17, 2018

Cold Midnight, Chapter 1 -- By Special Request!

I still have copies available of Cold Midnight, a "YA crossover" mystery set in 1921 in St. Johnsbury, Vermont, and based on a real "cold case" that the town never closed. By special request, here's chapter 1; you can get the softcover book from me, or the ebook online.

Cold Midnight

by Beth Kanell

Autumn 1921

Chapter 1

The

new rope worked much better than the knotted strips of sheets. And it was more

than twice as long.

In

the darkness behind the tenement house, untying the knot required her fingers

to dig and tug. Claire wished she’d brought a spike or even a nail. A nail –

there should be some scattered around on the ground. Easing quietly toward the

pool of light spilling from the downstairs parlor, Claire scuffed her shoes

until she felt something roll under them, and coaxed it along to where she

could see it and pick it up. She moved back against the wall and poked at the

knot with the iron point. Done!

Claire

was used to creeping down the back porches and only using her twisted line of

sheeting to drop down the last ten feet to the ground. It could hang there

until she returned. But the rope was different: she needed to take it with her

so she could get where she needed to go.

The

smell of tar hung thick in the warm night air. Main Street, just around the corner

from the tenement house, gleamed under its new coat of paving. No sense

stepping in the soft black ooze – Claire took the back route around the little

green-sided Christian Science church to the alley next to Willis’s hardware.

Carefully, she coiled the twenty feet of rope over her left shoulder. On

tiptoes, she ran up the three flights of fire stairs, avoiding the windows. Now

one long stretch, twenty feet high, separated her from the rooftop. She set her

fingers and toes into the brickwork and edged upward.

After

so many times crawling in darkness up the wall, with its fancy brick courses

and false window frames extending out as perfect footholds, the climb came

easily, up to the last bit where the roof hung over. Until now, the overhang

had defeated her. But this time, with her rope, she formed a sling and looped

it over a massive iron hook at the roof’s edge, built to grasp the snowload and

prevent it from falling on unsuspecting pedestrians in winter. The hook and the

rope sling would provide a way to let go of the wall and swing out.

She

tugged at the sling to make sure the knot would hold. It ought to: a square

knot, the way her father had shown her ages ago. Blue funk gripped her stomach

for a moment. She twisted her left hand around the rope sling, then snatched at

it with her right, flying loose from the wall. Four stories above the ground,

she dangled from her rope loop. Keep moving, she told herself, and heaved with

both arms, until she figured out how to launch her legs up. The scrape of her

boots against the roof startled her.

Don’t

stop now. It’s just like on the bars of the swing. Go!

Seconds

later, Claire stood on the roof of the Willis Block for the first time. The

size of it had always impressed her, as it stretched across five street-level

businesses. Her left arm burned from the rope’s friction, and she rubbed it

while she crouched and surveyed this new view of town. She peered down to be

sure nobody had seen or heard her – but the coast was clear.

First

she looked west, up the ridge, and oriented herself by the dark bulk of the

ancient pines above the town. She could see the distant cliffs block the starry

sky. The grand Bateman mansion spread solidly against the nearer slope, gas

lamps twinkling in the upper windows. There were no lights in the long glassed

greenhouse beside the mansion, but she saw small reflections of the bright

stars of early September.

Slowly,

Claire turned north, gazing past the short steeple of the Christian Science

church to see the massive stone structure of the North Church, then the brick

steeple of the Irish Catholic one. Beyond the handful of large homes at the

north end of town, the land rose to Mt. Pleasant Cemetery. She bent to rub one

knee, realizing she’d scraped that, too. Most likely her stockings would cover

it tomorrow, but she would need to be careful that no signs of her adventures

showed around her skirt and blouse, or her mother would grow suspicious.

Claire

swiveled south, toward the dark courthouse with its clock tower, then the

imposing halls of the Academy campus – the school halls that she already hated

after a single week of classes. Claire frowned fiercely, wishing they’d

disappear. For a moment she pondered what it would feel like to set them

aflame, the crisp, snapping fire engulfing them in seconds. But she knew it was

insane, a wild fantasy she’d never actually try. Her father had warned her

about fire-setters and their madness, back before the war, when he still talked

to her about real things.

Claire

closed her eyes and made the final quarter turn to face east, down the slope to

the downtown, the railroad, the river beyond. For a moment longer, she stood

blind, eyelids clamped together. She stretched her arms and hands wide, feeling

the cool night air between her fingers. She sniffed the breeze for river scent,

but she couldn’t find it. At last, she lowered her arms and opened her eyes.

Ah!

Cramped knuckles and scraped knees faded into insignificance. The town lay out

before her as if Claire were its only audience. Golden lamplight and silver

starlight splashed through and against windows. Halfway down the hill the

French Catholic church interrupted with its dark stone steeple. Closer to her,

someone pulled a curtain closed at an upper level. A late truck growled as it

pulled up Eastern Avenue toward Main Street. A dog began to bark angrily, a

second one yelped in conversation, and she caught a hint of a distant shouting

voice.

They

can’t hear me, she thought. They can’t see me. But they are mine, all mine.

The

bells of North Church tolled the hour: ten o’clock. She resolved to explore her

rooftops until midnight struck. Seven buildings linked together meant she could

walk all the way from here to the edge of the last roof above Eastern Avenue

itself. She twitched her rope to lay it flat on the first section of roof, then

started walking.

A

surprising number of objects rolled under her booted feet as she scuffed slowly

along. Although a rounded wedge of moon showed itself above the eastern

horizon, it didn’t light the roof. Claire could feel nails, and the snap of

twigs, and something soft that might be the remains of a bird. She tried to

avoid crushing whatever it was – the poor thing was most likely mangled enough.

Plus, she didn’t want to step in anything that would reek of decay. Continuing

to escape the house at night depended on not leaving traces that her mother

would notice. Her father, of course, wouldn’t notice if she put her muddiest

boots directly onto his lap.

Placing

a hand on a chimney top, she realized someone in the building had lit a fire.

Silly thing to do on such a warm night! But on second thought, perhaps it was

still warm from cooking supper. At home, supper could take place any time

between five and nine o’clock, depending on whether her mother felt exalted

that evening. Sometimes Claire’s mother set a row of candles along the table

and decorated it to resemble a feast, even when supper was only a reheated

slice of Sunday’s pork pie. She’d tear the bread apart with her long slender

fingers, instead of slicing it: “This was how his disciples recognized the

Lord,” she’d explain. “The way He broke the bread. After He rose again, of

course. Drink some wine, Claire. It’s not a sacrament like at church.”

“You’ve

watered it down,” her father would complain if he happened to be there. And

he’d take a draw from his flask instead, then forget to finish eating as he

shuffled out of the kitchen to the parlor and its darkness. Her mother’s

shoulders would slump, half from plain irritation, half from some deeper wound.

“Pray

for your father tonight,” she’d instruct Claire. “Forty ‘Hail Marys’ and then

the Our Father. He needs to go to confession.” Her voice louder, she’d repeat,

“Robert, you need to go to confession. You can’t take Holy Communion until

you’ve confessed to the priest.”

“Go

there yourself, eh,” her father would mumble back, and mutter a curse in French

just to annoy her, and drop heavily into his armchair without turning on a

lamp.

The

warm chimney also reminded Claire that she was walking above tenements where

people lived, over the shops. She hoped their ceilings muffled her footfalls.

Who lived in the rooms just beneath her? Mr. Willis, who owned the hardware?

No, he lived lower down, right above his store. This place must be his

brother’s, the one with all the small children.

The

urge seized her to peer through their windows and catch a glimpse of their

life. Could she reach the fire stairs behind this section of the store block?

She edged eastward, to the back end of the roof, and squinted into the darkness

below. She knew there was another set of stairs, but she had left her rope back

by the first set. Besides, she didn’t know how far this set went. She’d have to

inspect it by daylight before risking the drop.

Back

to the center again, then south, across the roof of the ladies’ clothing store.

Then the two sections joined together below into the grocery and what must be

the little bakery. At last she knew she stood above the photographer’s studio.

The rising moon lit a low wall in front of her, where the roofline rose to go

across the bank at the corner, with a false row of windows along the front.

The

wide, open space of Eastern Avenue yawned in the darkness below. Across the way

was the park, and beyond that, the courthouse. A movement among the bushes

caught her eye: a dog, scruffy and slow. She could barely hear its faint

snuffling.

When

the whistling started, she jerked in place, grabbing the chimney nearest to her

to stop a wave of vertigo. Her head spun. The sweet pure whistle rose in a tune

she knew: “Listen to the mockingbird,” it trilled. The strangeness of it in her

hard-luck town, her town viewed from its high Main Street roofs, nearly blinded

her. Then the whistle began to dance around the tune, ornamenting it, pouring

it into the darkness as if night were shaped with a space that belonged to

music and to joy.

Just

before the tune ended, she realized a boy in dark clothing, with the bulk of a

jacket slung over his shoulder, had emerged from the shadows of the park and

was walking into the long alley behind the store buildings. By the time she

thought to cross the roof and look directly down the side of the building, he

had vanished into the darkness, along with his melody.

In

the boy’s absence, the town laid itself out again, nearly silent. Claire walked

the roof in the other direction, back to where her rope lay folded, getting the

feel of it into her feet. The false windows rising above the front of the

photographer’s building offered a good place to perch, so she circled back

there. Where her hand rested on the brick wall, she felt lumps like chewing

gum. Bird droppings. She scrubbed her hand against her sweater and stuffed it

into a pocket, where her handkerchief sat in a ball.

Why would someone

build a row of false window arches at the front of a building? Just to make it

look taller? There was no glass, nothing behind them except the roof itself.

Claire fingered the brick surface carefully before climbing inside an arch, to

sit curled within the chilly but strong framework. Looking up the hillside to

the west, with the Bateman mansion in the center of her view, she watched the

upstairs lamps begin to go out, one after another in a line. The last one

lingered a few minutes longer. Someone setting aside his or her clothes, no

doubt. Would it be Mr. Bateman himself? No, that upper room must belong to a

maid or the cook.

Below

her, footsteps pattered along Main Street. Somebody was running there, keeping

close to the block of buildings. She turned to hook an arm more firmly, then

leaned cautiously from her position inside the arch, not wanting to make a

sound.

The

person in the darkness reached the corner of Eastern Avenue and Claire could

see enough to be sure it was a man or a very tall, older boy. His arms were

pumping and she could hear his breath, ragged and rapid. From above, the cap on

his head looked like one of her father’s uniform caps. He stopped, reached out,

and pulled the hammer of the fire alarm box. Then he ran.

Bells

rang loudly in the firehouse down the road and in the Methodist church steeple.

Lamps flared higher. Men shouted, and a truck engine roared to life. Claire

pressed her back against the wall. Crouching behind the brick edging, she

watched: one truck, the pumper; then the second one, its ladders hanging off the

end; four men clutching the rails. A fifth man stood by the open doorway,

staring down the road, then bolted back inside, shouting again.

A

harsh charcoal smell filled the night, much stronger than chimney smoke. Not

far from her, metal on metal screeched and more shouts echoed as the new fire

trucks halted just beyond the courthouse. Hunched low, keeping her balance, she

ran to the south end of the line of buildings and saw a red flicker of flame at

the side of the boarding house beyond the courthouse park.

Her

father would be there soon! The fire bells surely had summoned him by now. Any

moment, he might wake her mother, too. Claire needed to return to her bed and

be under the covers in case they looked into her room.

She

fled back north along the roofs, fumbled for the loops of her rope, and swung

wildly for the steps below.

Tuesday, July 3, 2018

Independence Day for Book Lovers

Independence Day is such a great holiday in Vermont -- community events, meals shared, LOTS of pies and ice cream, and fireworks in all directions.

Many Vermont people will take part in the annual readings from Frederick Douglass's poignant and powerful speech, "What to the Negro Is the Fourth of July?" (Find some of those events here.) A few years ago, I discovered Frederick Douglass had actually spoken in nearby St. Johnsbury, Vermont -- so glad to know this!

I'll also be burrowing into writers' investigations of "independence" in many books, and I appreciated finding this in my e-mail today from New York Times editor Rumaan Alam:

-->

-->

Many Vermont people will take part in the annual readings from Frederick Douglass's poignant and powerful speech, "What to the Negro Is the Fourth of July?" (Find some of those events here.) A few years ago, I discovered Frederick Douglass had actually spoken in nearby St. Johnsbury, Vermont -- so glad to know this!

I'll also be burrowing into writers' investigations of "independence" in many books, and I appreciated finding this in my e-mail today from New York Times editor Rumaan Alam:

Many great books for children are grounded in American history. When I was younger, two of my favorites were Robert Lawson’s “Mr. Revere and I” and “Ben and Me,” which imagine the horse that Paul Revere rode into history and a mouse who inspired Ben Franklin’s greatest innovations. I’ve got two young readers of my own, now, and one of the books I most enjoy sharing with them is “I, Too, Am America,” which marries illustrations by Bryan Collier with the enduring text by Langston Hughes. My boys are also huge fans of everything Maira Kalman does; she’s written and illustrated two children’s biographies of great presidents: Thomas Jefferson: Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Everything and Looking at Lincoln. (Kalman has also published a wonderful illustrated book for adults that includes her thoughts on those presidents and much more, “And the Pursuit of Everything,” which I recommend highly.)

So of course, I wrote back to Mr. Alam:

I like your Independence Day suggestions! Here are a couple more, since straightening out US history is so important: Never Caught: The Washingtons' Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge (by Erica Armstrong Dunbar); New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America (by Wendy Warren); The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism (by Edward E. Baptist).These interest me because I'm trying to straighten out the picture of Vermont in the years before the Civil War, in The Long Shadow (by Beth Kanell, naturally), which is Book One of the Winds of Freedom (Five Star / Cengage).

What new insight into American history have you found this year? Was a well-written, well-researched book involved?

Happy Fourth of July!

Happy Fourth of July!

Thursday, March 29, 2018

Updated: Talking about THE LONG SHADOW: Events

“One

can practically smell the stench of the town drunk and feel the cold in

the root cellars . . . the characters are well-drawn. Both adults and

teens should enjoy

the story and look forward to Kanell’s next book.”

-- Booklist, The American Library Association

One of the pleasures of bringing out a new book is bringing it TO people! I'm looking forward to sharing some of the stories that led to THE LONG SHADOW as I meet with groups over the next few months. Here's the schedule for the near future:

Saturday September 1: Barnet Historical Society -- more details soon!

And I'll be speaking at the New England Crime Bake in November. Lots to think about before then, though.

Watch for news about the Shadow Photo Collection ...

Sunday, February 18, 2018

Saying Goodbye to the Underground Railroad Myths

One of the hard parts of growing wiser and kinder is saying goodbye to some things we once thought were wise and kind -- but turned out not to be. For me, one of the sad farewells to make involved the Little House books of Laura Ingalls Wilder ... a series I enjoyed as a youngster, imagining myself as part of the cozy little family that moved West along with the American frontier.

When I "grew up" in terms of historical fiction, I began to realize the harm those books can do, in particular Laura's mother's opinion that Native Americans were dangerous and should be killed -- after, of course, depriving them of their lands and customs. It was a painful change to make, to see the books as only "reference" for folk ways and for traditional American White bigotry. It still hurts.

With that new awareness came the realization that many books for children in particular embrace myths that do harm. The books pictured here -- one of which is actually sold as nonfiction -- have problems in terms of the history they teach and the myths they encourage. Because I care about young readers having good books available that show more truthful accounts of the past, I dug into both American and Vermont research on the 1800s. And then I got to work and wrote THE LONG SHADOW, an adventure of three teenage girls in 1850 in Vermont's Northeast Kingdom. The book will be published in about 8 weeks, on April 18, 2018.

With that new awareness came the realization that many books for children in particular embrace myths that do harm. The books pictured here -- one of which is actually sold as nonfiction -- have problems in terms of the history they teach and the myths they encourage. Because I care about young readers having good books available that show more truthful accounts of the past, I dug into both American and Vermont research on the 1800s. And then I got to work and wrote THE LONG SHADOW, an adventure of three teenage girls in 1850 in Vermont's Northeast Kingdom. The book will be published in about 8 weeks, on April 18, 2018.For a quick summary of "what's wrong with the Underground Railroad myths," check this succinct and authoritative version provided by Prof. Henry Louis Gates.

And for more discussion, join me to learn about my new book at a local bookstore, or on the radio, or invite me to bring the conversation to your club, church, or classroom. After all -- that's why I wrote this book. So that you and I could talk about it all.

Monday, February 12, 2018

Lincoln's Birthday ... and Thaddeus Stevens on My Mind

"President's Day" is still a week away, but today, February 12, is the date that is Abraham Lincoln's birthday. When I was growing up, schools celebrated it -- not as a day off, but as a day to pay attention.

Today in our era marked by harsh political conflict and skyrocketing awareness of the way America's centuries of enslavement have injured our people, it's a good day for learning more about our past and choosing ways to make the present and future better, I believe.

So I paused this morning to check what Abraham Lincoln was doing in 1850, the year when my "Winds of Freedom" series opens with the book The Long Shadow (publication date April 18, 2018). In that year, Lincoln was still practicing law in Springfield, Illinois, where he took on quite a few transportation cases. He also gained a patent of his own for a boating invention. He'd already served one term as a legislator, and opposed the land grab of the Mexican-American war; that war ended two years earlier, marking his first contribution to national affairs. He wouldn't speak out again until 1854.

But in 1850, an ardent freedom fighter from Vermont, transplanted to Pennsylvania, took a powerful stance in Congress to oppose slavery. That voice came from Thaddeus Stevens, and it echoes many others, especially the voices of America's Quakers, who pointed bluntly to the evil of humans being "owned" by others. "Chattel slavery," they spoke of -- "chattel" refers to personal property, and unlike, say, indentured servants, chattel slaves could be transferred by will or by bill of sale.

Yes, you'll find actions by Thaddeus Stevens influencing Vermont village life in The Long Shadow. Importantly, the choices taking place in this book are made by women who choose to take action -- protagonist Alice Sanborn, her best friend Jerusha, and their younger and very dear friend Sarah, with her dark skin and desperate longing for her family, still enslaved but with hope of purchasing their freedom. And Miss Ruth Farrow and the Mero family -- historically "real" Black Americans who lived in my part of Vermont in 1850.

Yes, you'll find actions by Thaddeus Stevens influencing Vermont village life in The Long Shadow. Importantly, the choices taking place in this book are made by women who choose to take action -- protagonist Alice Sanborn, her best friend Jerusha, and their younger and very dear friend Sarah, with her dark skin and desperate longing for her family, still enslaved but with hope of purchasing their freedom. And Miss Ruth Farrow and the Mero family -- historically "real" Black Americans who lived in my part of Vermont in 1850.Each of us has something to contribute to making the world a more just and valued place to live. For me, it's speaking of how things really were in 1850 -- here in the Green Mountains of Vermont, where reading the words of Thaddeus Stevens gave a fierce and upright example.

Wednesday, January 17, 2018

An Update to Eleanor Perry Conwell's Provincetown Story

Research always makes up the background of the Vermont fiction that I write. A few years ago, I pulled out "consumption" statistics for this area in the early 1900s -- that was the final stage of tuberculosis (TB), in general. Last week, I found the death record for 4-great grandmother Eleanor Perry Conwell, whose "portrait" (by William Matthew Prior) goes to auction at Sotheby's this week. What a shock to see the cause listed as consumption. I hope the sale of her portrait will help her story of courage and New England initiative to live on.

Research always makes up the background of the Vermont fiction that I write. A few years ago, I pulled out "consumption" statistics for this area in the early 1900s -- that was the final stage of tuberculosis (TB), in general. Last week, I found the death record for 4-great grandmother Eleanor Perry Conwell, whose "portrait" (by William Matthew Prior) goes to auction at Sotheby's this week. What a shock to see the cause listed as consumption. I hope the sale of her portrait will help her story of courage and New England initiative to live on.Tuesday, January 16, 2018

The Weather Inside and Out (A Robert Frost Moment)

I have three favorite Frost poems, and one matters a lot to me today: "Tree at My Window." You might be aware that it's a violation of copyright to post an entire poem by someone else (actually most people don't know this! I found out when I erred by posting one, blush). So I'll just give the final verse of this Frost poem here, which begins with the poet's persona talking with the tree just outside his window:

That day she put our heads together,Out on the mountainside today, the snow keeps taking different shades of white, oyster, light gray, even a very pale blue, as the clouds thin and thicken again in front of the well-hidden sun. A few snowflakes fall occasionally; steadier snow is expected this evening, when I'll be doing some errands of my own, so I'm paying attention to the forecast. It's a classic January day, but it's also a bit March-ish, that sense that the snow's been here a long time and isn't in any hurry to leave.

Fate had her imagination about her,

Your head so much concerned with outer,

Mine with inner, weather.

Interior weather: I've just let go of a manuscript that's lived in my heart (and on scraps of paper, in notebooks, and on the computer screen) for three years. It's both wonder-filled and terrifying to send it out into the world, where the staff of a publisher will look at it in very different ways from mine.

At these moments, I usually change the writing room, to find fresh vision and focus for the next effort. I have three books being built now: one just at the starting point, with the title "A Necessary Holiness"; another, poems of prayer and praise, perhaps half assembled; and the third, the set of stories I completed as 2017 raced to an end, where a good two days of rigorous revision should wrap up the project. But you know how life is ... setting aside those two important days will take planning.

So the room, especially the desk and walls, become part of the preparation. The photos here show what I've changed -- and where I'm going, I think.

All of this is especially necessary because I'm also stepping into the final 100 days before publication of my new adventure novel The Long Shadow and I'll be talking about that book often ... but the deep digging of the work-in-progress must continue. Wish me luck. No, on second thought, please wish me a well-crafted balance. And good weather.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Published! Two of My Sonnets, in ALL THE WORLD'S A PAGE

Of course I read Shakespeare's sonnets in high school, and liked some -- although at the time, I had little experience of trying to de...

-

Climate collapse, floods and fires, political divisions, wars and devastation—in America, it's not uncommon for people to feel like it...

-

Last year it looked like our region of Vermont had lost, forever, a tourist icon we'd enjoyed for decades: the Route 2 gift shop ca...