|

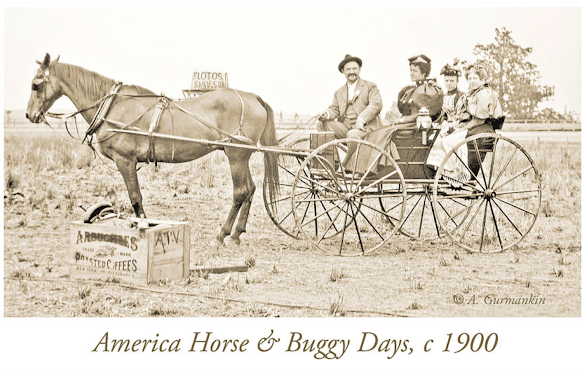

| In the collection of the Shelburne Museum. No brake! |

Within the next week or so, I expect to finish writing the third book in my Winds of Freedom series. It's set in Vermont in 1854, and it's had a working title of Kindred Hearts, but I'm quite sure that will change. I'm waiting until the last plot twist, passion for the future, and page of dialogue are done. Then I'll brainstorm titles.

Meanwhile, I've been working hard at learning how to hitch a horse to a buggy and drive it! Somehow this was not mentioned in any of my history courses. Luckily, although Vermont winter isn't exactly conducive to asking a neighbor to show me the reins, there are many engrossing YouTube videos that show how to put on a harness, how to attach the "hames," and much more.

Then I've also been taking a crash course (self-taught) in buggies themselves. My protagonists, Almyra and Susannah, are fortunate to have access to the resources of a small livery stable at their village inn. That means that sometimes they don't have the kind of buggy or carriage they want -- and sometimes they end up on horseback themselves. Learning about riding with a sidesaddle was another treat of this book!

Here are some of the images I've studied, working out who puts her foot where, how much risk there is that she'll show a shocking amount of her ankle or petticoat, and more.

Thanks in advance to Fran and Bert Fissette, neighbors who've loved their horses and have answered some of my questions via text, so I could keep typing!

Circ1 1915:Late 1850s: