The series is piling up nicely. These are first drafts; I won't go to revisions for a while yet. I love the way first drafts pile up, like raked leaves, that same dry scent ...

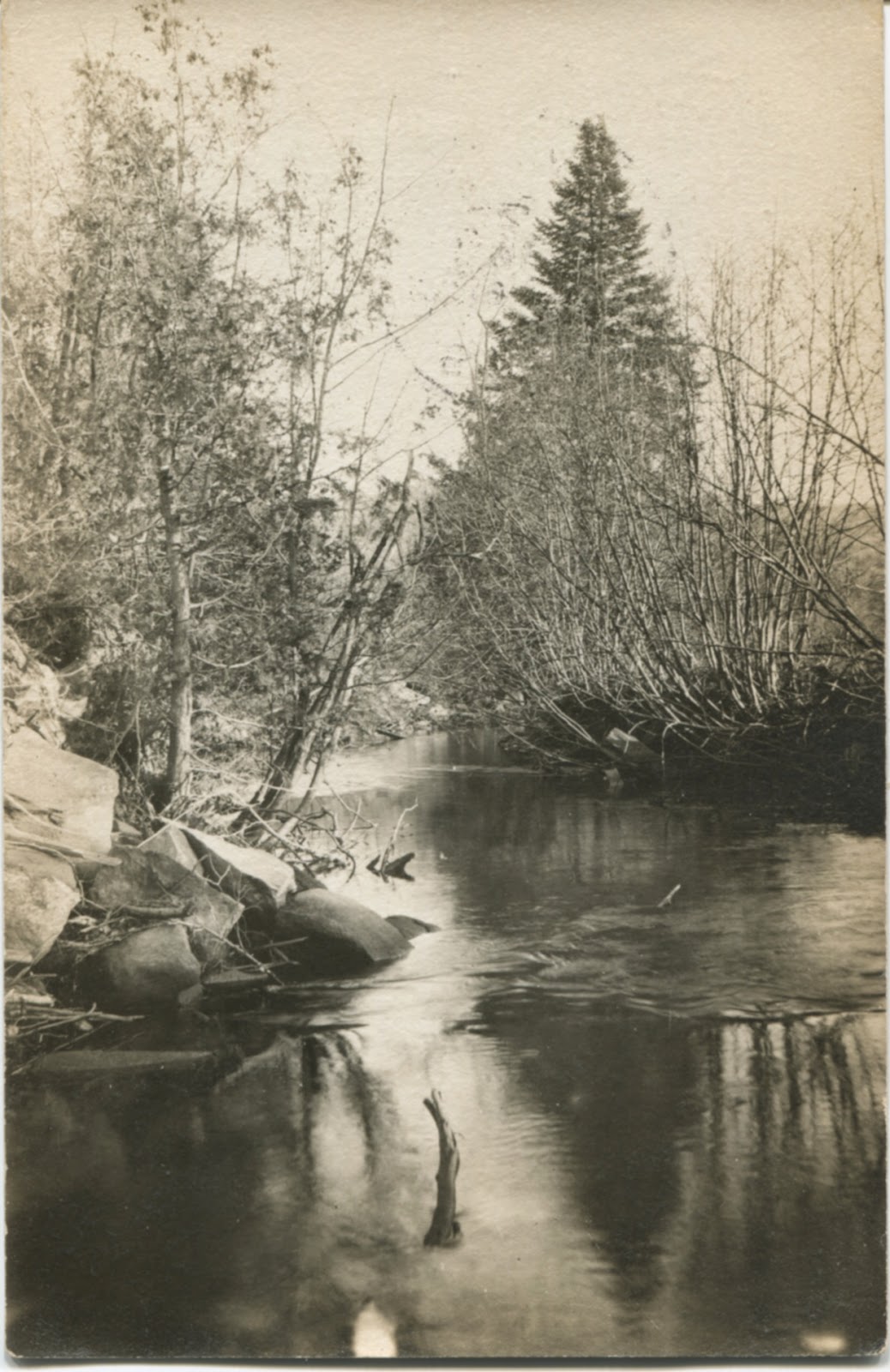

The scent of the autumn woods, a leaf

caught in my hair – did we choose the place,

or did it pull us relentlessly (it was always

meant to be: this hunger you wake in me,

this place in the chest where October lives).

Once upon a time I thought each question

had to be asked. Now, I only want your mouth

against mine, your pulse, this answer,

real as the twig caught against my shoulder.

Say “maple.” Say “birch.” Say “yes.”

-- BK, 10/30/15

A Visit to the Old Place

Every year around this time

with the harvest in, oats, carrots, apples

dry leaves crunching underfoot

we pull the truck out of the barn.

There is room behind the seats for the big thermos

and sandwiches, whose fragrance

fills the space between us: garlic, onion, salt

(oh yes, salt asserts its own fragrance)

and behind us the house diminishes until

the road bends – we enter that wilderness

of need and complaint. Why would God invent

traffic jams, road construction, yellow diggers

surrounded by supervisors in orange vets –

things we have not missed during our autumn.

But we missed the home place, the well of grace.

He drives. I comment. “Things have grown up so much.”

There’s no answer to change, except to grow apples

There’s no answer to change, except to grow apples

somewhere else. Shopping mall, parking strip,

cluster of seedy brick shops. Declare MacIntosh. Cortland.

Golden Delicious. Are we there yet? He watches

the odometer, brakes, says “Here. It was here.”

One iron gate hangs loose from a stone pillar,

broken pavement beyond it. A red plastic cup and

bare and thin as arms escaping a white gown. Some sad smell.

“The angel stood: there.”

-- BK 11/7/2015

Hungry During Deer Season

Going “back to the land” meant hunting: the awkward feel

of cold steel, balancing the rifle, checking the calendar.

That first season of daily hunts, though, the man in my life

did everything the hard way. No snow to track with.

No high-tech clothing for warmth. Each day, perched in a

tree

with a bow and arrows, tested at the suburban archery range.

And on the last day of the season, mid afternoon,

he ran breathless out of the forest, arms waving, stumbling:

“Come with,” he gasped, “need you. Carry.”

I wrapped my coat around my swollen belly and followed.

It was a small deer, as deer go. But male, and with antlers,

and the paper tag already fastened to the corpse

as if it needed a toe tag but the hoof couldn’t cooperate:

body, cooling, heavy with the day’s grazing. Close up,

it wasn’t Bambi at all, but coarse-haired, wild, muscled.

“Take the front legs,” my hunter directed me. “Don’t bump

the head into any trees. Lift.”

Even dead, the round eyes shone, ready to capture

the last sunlight. The sun sank into cold twilight

and we lifted, tugged, staggered. How heavy it was,

that awkward, stiffening body. When I stumbled,

he cried out, “Careful! Don’t hurt him!” But my hands

needed to release the hairy skin, the bony leg,

needed to rub in habit and comfort against

the baby bump. Oh child to come, oh little one,

already it’s you, most important in my life.

Not yet for him, bearing his first deer, his heart

wild in triumph and joy – yet the little fists in my belly

struck outward, toward that man becoming a father.

“I need,” I said. “I need to breathe. I need to stop

for a moment to rest my hands.” And my heart.

Supper to make, but first the kill to report,

and the body to raise high into a tree,

its belly slit, its liver sliced and sizzling in a cast-iron

pan.

From here onward, it’s all the other wants

that I’m hearing. I cook. I feed. When the baby comes,

it will be strong, healthy. Hungry.

-- BK 11/6/15