As I write THIS ARDENT FLAME, set in northern Vermont in 1852, I spend a lot of time in research -- but not just exploring this pre-Civil War decade of ferment. In order to understand the thinking and discussions of the time, I often backtrack to the War of Independence and the strong-minded individuals who voiced their dreams for this new nation, built from a set of very different colonies and then growing by annexation of territory (and almost always while ignoring the history and rights of Indigenous peoples).

This week I'm reading Compassionate Stranger: Asenath Nicholson and the Great Irish Famine, by Maureen O'Rourke Murphy. One reason to read the book is as background for how the characters in THIS ARDENT FLAME deal with the Irish immigrants arriving in Vermont at the time. Another is that Asenath Nicholson, an activist of the first half of the 1800s, was born and raised in Chelsea, Vermont, not far from the Northeast Kingdom. (I've spent many hours there as the mom of an actor in a Jay Craven/Howard Frank Mosher film. Where the Rivers Flow North.)

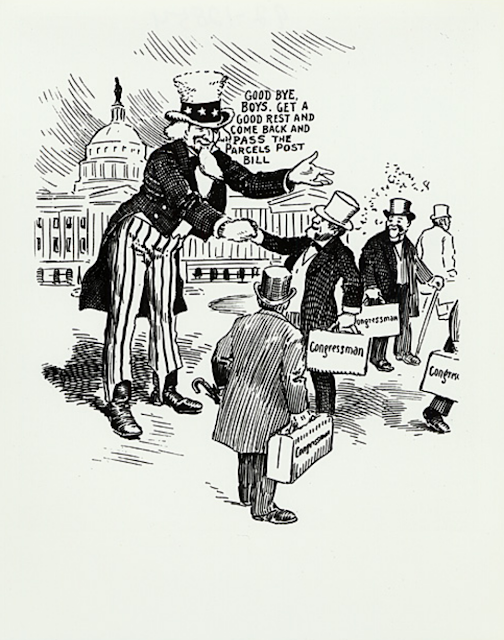

Every detail in the book takes me digging for more details elsewhere, and this morning I "dug into" Sunday mail delivery. I was surprised to learn that it was routine in our nation's first century: It was considered essential for commerce! Moreover, the 1820s/1830s movement to end Sunday mail delivery came out of a small group with religious passions and especially religious bias -- against those Irish and other Catholic immigrants, who often used their "day of rest" to feast, gather, and rejoice, rather than to endure the silent solemnity of a Puritan-style Sabbath.

The post office with its mandatory Sunday opening (required by law to be open at least one hour each Sunday) became a social location. Not only did men gather there to pick up their letters and commercial orders, but they also often sat down to socialize, drink, and play cards. This horrified those who took their Sunday worship more seriously. Interestingly, these horrified individuals were often the same ones pursuing the Abolition of slavery, out of the same Christian beliefs!

Thus, Arthur Tappan, an ardent abolitionist of both New York City and New Haven, CT, would raise as much anger by his "Sunday mail laws" campaign as by his campaign to end slavery, and his brother Lewis, campaigning the same way, had his house broken into in 1834 by an angry mob.

Only 7% of the nation claimed strong religious ties at the time, and most opposed shutting down the post office on Sundays. The invention of the telegraph in the 1840s would ease the commercial necessity of Sunday mails. But the legislation to close the post office on Sundays would not be passed until 1912, and part of the opposition to it lay in favoring one religion over another, counter to the definitive statement of the Constitution that insisted the new nation not pick and choose. (Arguments included the belief that Sunday closing of the postal service would then lead to Saturday closing on behalf of the Jewish Sabbath, to be fair!)

What eventually tipped the nation to passing the closure laws was a combination of two pressures: postal workers wanting a day off like everyone else, and trading the closure for the new service of Parcel Post: being able to handle packages routinely.

That's a lot to think about, in the context of this week's political talk about Amazon, postal rates, and Sunday deliveries that have now resumed!

Vermont author Beth Kanell is intrigued by poetry, history, mystery, and the things we are all willing to sacrifice for -- at any age.

Wednesday, December 26, 2018

Sunday, December 9, 2018

Crossing Paths with Franklin Benjamin Gage of East St Johnsbury

Although it's barely a whistlestop* now, with just a post office and a church and a "free library" on the post office porch -- plus the significant Peter and Polly Park, which I'll write about at another time -- East St Johnsbury was once a hub of manufacture and business. The significant Fairbanks family that nurtured both jobs and culture for the area erected its first mill on the Moose River in East St Johnsbury. Actually in the early days this was "St Johnsbury East" or just "East Village." And it prospered.

That prosperity and the related emphasis on education were in the background of a youth named Franklin Benjamin Gage, born in the village in 1824. He became a significant inventor in photo processes, and created both portraits and landscape images. I'm enamored of his stereo views of the region, which have become hard to find.

Shown here is a child portrait -- could it be your great-great-great-grandparent? -- probably made in Gage's studio in St. Johnsbury proper. On the reverse, he calls it an "ebonytype": a fancy name for a way of presenting the work that may have emphasized the sharp contrast of black and white in the original portrait. It's hard to tell now ... "ebonytype" doesn't have a definition that I've found, and is only mentioned in a wonderful article on Gage, from which I draw this quote:

If this IS your four-greats grandparent, please do let me know. I'd love to attach a name to the face.

*Whistlestop: a railroad term. Also pertinent to the article I spent yesterday researching and drafting. You'll see it soon.

[Thanks, Dave Kanell, for the images!]

That prosperity and the related emphasis on education were in the background of a youth named Franklin Benjamin Gage, born in the village in 1824. He became a significant inventor in photo processes, and created both portraits and landscape images. I'm enamored of his stereo views of the region, which have become hard to find.

Shown here is a child portrait -- could it be your great-great-great-grandparent? -- probably made in Gage's studio in St. Johnsbury proper. On the reverse, he calls it an "ebonytype": a fancy name for a way of presenting the work that may have emphasized the sharp contrast of black and white in the original portrait. It's hard to tell now ... "ebonytype" doesn't have a definition that I've found, and is only mentioned in a wonderful article on Gage, from which I draw this quote:

The highly researched piece on Gage is authored by Bill Johnson and Susie Cohen -- I don't know who they were/are, and they stopped posting their writing about vintage photos five years ago. But I keep returning to the article, and now it has added meaning because the prime of F. B. Gage's life overlaps the period that's coming to life in my in-progress book, THIS ARDENT FLAME (second in the Winds of Freedom series from Five Star/Cengage). So I am thinking about what Gage may have seen in this image, and why he chose it to promote his work.By 1856 Gage advertised that his was the largest photographic establishment in the state of Vermont; at first offering daguerreotypes and then adding all the modern processes and styles as they became available – ambrotypes, mezzotypes, ebonytypes, cartes-de-visite, cabinet portraits, and so on, as well as displaying and selling his stereo views.

If this IS your four-greats grandparent, please do let me know. I'd love to attach a name to the face.

*Whistlestop: a railroad term. Also pertinent to the article I spent yesterday researching and drafting. You'll see it soon.

[Thanks, Dave Kanell, for the images!]

Tuesday, December 4, 2018

Ruffed Grouse, or Partridge (Pa'tridge)?

One of the challenges of writing a novel set in 1852 is the details that aren't recorded, but that I still want to get "historically accurate" for the story. Today's puzzlement is how to talk about the wild bird known to American colonists, based on their British experience, as partridge -- but corrected in name to ruffed grouse. John J. Audubon painted the birds (see above). And Karen A. Bordeau of the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department also wrote this in 2015:

And the New International Encyclopedia of 1917 says this:

So, what do my characters call these birds? That's in chapter 4 of THIS ARDENT FLAME (Book 2 of Winds of Freedom).

Regulation of grouse hunting received no attention for a long period. The first act protecting birds was passed in 1842, affording a breeding and rearing season free from molestation. They could be legally taken between September 1 and April 1, and permission of the landowner was required for hunting.

The regulation was repealed after four years, and grouse remained unprotected until 1862. The second law protecting grouse, passed in 1862, established a shorter season – September 1-February 28 – and four years later hunting was further curtailed by closing the season on January 31. Snaring had been a popular method of capture, and in 1885, was forbidden. By 1929, grouse were so rare all over the state that the Legislature completely closed the season in Coos County on the Canadian border, and in Cheshire County bordering Massachusetts.

And the New International Encyclopedia of 1917 says this:

So, what do my characters call these birds? That's in chapter 4 of THIS ARDENT FLAME (Book 2 of Winds of Freedom).

Sunday, December 2, 2018

Review of THE LONG SHADOW in Vermont History, Summer/Fall 2018, Social Studies Focus

One of the best tests of a historical Vermont novel with teen protagonists takes place when a social studies teacher -- a professional in the field -- sits down to read it. So I am hugely grateful and honored that Christine Smith, a teacher-librarian at Spaulding High School in Barre, Vermont, and president of the Vermont Alliance of the Social Studies (VASS), chose to read and review THE LONG SHADOW for the summer/fall 2018 issue of Vermont History, the journal of the Vermont Historical Society. I'm posting the review here -- seeing this in print is one of the great benefits of being a member of the Vermont Historical Society. Other articles in this issue focus on Burlington's ethnic communities, a Vermont steamboat pioneer, and Revolution-era hero Seth Warner. All worth reading!

My Brain Is Back in 1852 (Writing THIS ARDENT FLAME)

Dishes are stacked a little higher than usual. There's dust under the bed. But the chapters are unfolding, each page a marvel as I "discover" where the new book is going. My feet and my brain are in 1852 (fear not, my heart's still with my honey in 2018, and I can still cook).

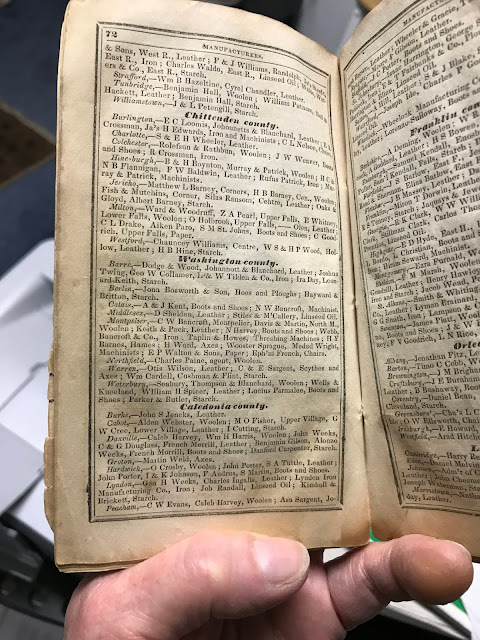

Just so you can see what it's like -- at one moment I'm tapping out dialogue and moving the characters to the next scene. And then, quick, it's time to dash back into the research, like these marvelous pages from the 1854 edition of Walton's Register -- a business directory for Vermont that reveals much, much more than who owns what.

Just so you can see what it's like -- at one moment I'm tapping out dialogue and moving the characters to the next scene. And then, quick, it's time to dash back into the research, like these marvelous pages from the 1854 edition of Walton's Register -- a business directory for Vermont that reveals much, much more than who owns what.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Published! Two of My Sonnets, in ALL THE WORLD'S A PAGE

Of course I read Shakespeare's sonnets in high school, and liked some -- although at the time, I had little experience of trying to de...

-

Climate collapse, floods and fires, political divisions, wars and devastation—in America, it's not uncommon for people to feel like it...

-

Last year it looked like our region of Vermont had lost, forever, a tourist icon we'd enjoyed for decades: the Route 2 gift shop ca...