As I write THIS ARDENT FLAME, set in northern Vermont in 1852, I spend a lot of time in research -- but not just exploring this pre-Civil War decade of ferment. In order to understand the thinking and discussions of the time, I often backtrack to the War of Independence and the strong-minded individuals who voiced their dreams for this new nation, built from a set of very different colonies and then growing by annexation of territory (and almost always while ignoring the history and rights of Indigenous peoples).

This week I'm reading Compassionate Stranger: Asenath Nicholson and the Great Irish Famine, by Maureen O'Rourke Murphy. One reason to read the book is as background for how the characters in THIS ARDENT FLAME deal with the Irish immigrants arriving in Vermont at the time. Another is that Asenath Nicholson, an activist of the first half of the 1800s, was born and raised in Chelsea, Vermont, not far from the Northeast Kingdom. (I've spent many hours there as the mom of an actor in a Jay Craven/Howard Frank Mosher film. Where the Rivers Flow North.)

Every detail in the book takes me digging for more details elsewhere, and this morning I "dug into" Sunday mail delivery. I was surprised to learn that it was routine in our nation's first century: It was considered essential for commerce! Moreover, the 1820s/1830s movement to end Sunday mail delivery came out of a small group with religious passions and especially religious bias -- against those Irish and other Catholic immigrants, who often used their "day of rest" to feast, gather, and rejoice, rather than to endure the silent solemnity of a Puritan-style Sabbath.

The post office with its mandatory Sunday opening (required by law to be open at least one hour each Sunday) became a social location. Not only did men gather there to pick up their letters and commercial orders, but they also often sat down to socialize, drink, and play cards. This horrified those who took their Sunday worship more seriously. Interestingly, these horrified individuals were often the same ones pursuing the Abolition of slavery, out of the same Christian beliefs!

Thus, Arthur Tappan, an ardent abolitionist of both New York City and New Haven, CT, would raise as much anger by his "Sunday mail laws" campaign as by his campaign to end slavery, and his brother Lewis, campaigning the same way, had his house broken into in 1834 by an angry mob.

Only 7% of the nation claimed strong religious ties at the time, and most opposed shutting down the post office on Sundays. The invention of the telegraph in the 1840s would ease the commercial necessity of Sunday mails. But the legislation to close the post office on Sundays would not be passed until 1912, and part of the opposition to it lay in favoring one religion over another, counter to the definitive statement of the Constitution that insisted the new nation not pick and choose. (Arguments included the belief that Sunday closing of the postal service would then lead to Saturday closing on behalf of the Jewish Sabbath, to be fair!)

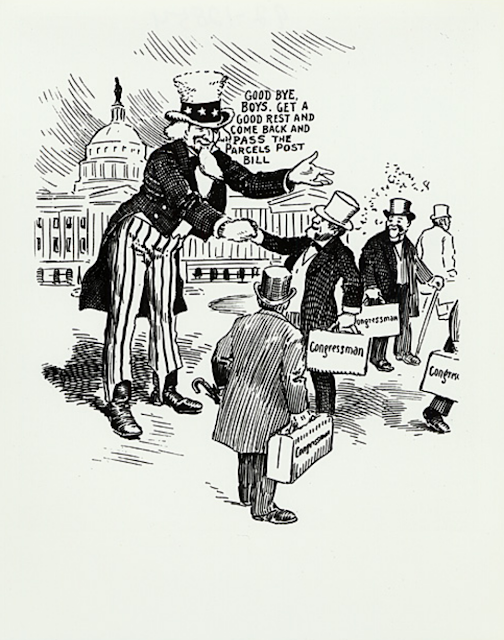

What eventually tipped the nation to passing the closure laws was a combination of two pressures: postal workers wanting a day off like everyone else, and trading the closure for the new service of Parcel Post: being able to handle packages routinely.

That's a lot to think about, in the context of this week's political talk about Amazon, postal rates, and Sunday deliveries that have now resumed!

Vermont author Beth Kanell is intrigued by poetry, history, mystery, and the things we are all willing to sacrifice for -- at any age.

Wednesday, December 26, 2018

Learning the 1800s: Sunday Mail Delivery

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

The Astonishing Variations of "Poetry World"

My first published poem, "October," came out in YANKEE magazine -- which meant a lot to me (and still does), because more than any...

-

Climate collapse, floods and fires, political divisions, wars and devastation—in America, it's not uncommon for people to feel like it...

-

Time chugs along -- I will soon mark 50 years of living in my adopted state among the Green Mountains and the many rivers. When I first arri...

No comments:

Post a Comment